I travel a lot for work which means that more often than not, at least twice a week I find myself in a taxi headed to or coming from the airport. Ordinarily I avoid small talk with cab drivers – not to be rude, but honestly I’m just trying to catch my flight or go home to sleep. The predictable conversational hailstorm of, “How’s your day?” or “But you don’t sound African!” takes away from what I consider to be a sacred transition to the weekend.

Recently on a cab ride to the Boston airport, I got into a conversation with a French-Algerian yellow cabbie who had clearly been waiting for a fellow (read: “relatable”) immigrant to unburden himself of something that had obviously been on his mind for a while.

Abdulaziz (the cabbie) had been home to visit his family twice over the past couple of years, both times flying the 11 hours on Air France to Algiers, connecting through Charles de Gaulle. He described his home-town with the romanticism you’d expect from a nostalgic émigré: Oran perched serenely on the deep blue waters of the Mediterranean; the city’s architecture an homage to an often infamous French, Spanish, Ottoman, and Berber history.

His tone soured as he described the first return journey to the United States. A US green card holder, he travelled on an Algerian passport, and it was this leaf-green booklet that he presented when passing through security at Logan airport. Abdulaziz from the People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria.

You know what came next: “random” selection for further questioning in a back room.

It wasn’t the size of the room, the off-grey walls, or the aggressive interrogator that got to him. It was the assumed guilt implied by the invasive line of questioning. Previous travel, marriage, occupation, education, everything was open for inquiry. He grew more agitated as he spoke; our car speed increased. I put on my seat-belt.

He then told me of the second trip, after completing his US naturalization, after replacing his Algerian passport with a shiny blue one just in time to return to Oran for a family affair. His return journey this time was entirely different – no random selection, no squinty eyes when he said his name. He even got a “welcome home, sir,” from a customs and border protection officer.

“What is the difference between Abdulaziz from Algeria and Abdulaziz from United States?” he asked me. “It is still same me!”

Agreed.

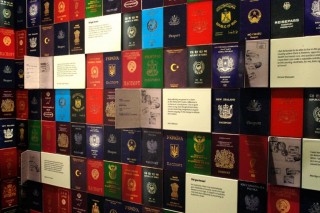

A passport is “an official document issued by the government of a country to one of its citizens and, varying from country to country, authorizing travel to foreign countries and authenticating the bearer’s identity, citizenship, right to protection while abroad, and right to re-enter his or her native country.”

Nonsense.

A passport is swag. It is a mark of pedigree. It guarantees the holder rights and protection, sure, but more immediately, a certain kind of passport implies certain things about the holder in much the same way a Rolex implies you are rich or a posh British accent implies intelligence on most terrible TV series.

The color of one’s passport allows for silly (and often loud) statements like “DO YOU KNOW WHO I AM?!” (The irony of this question, posed while holding official identification, is hardly lost on me). Men and women now rank potential spouses based on the flexibility of their paper-work, and even Wande Coal understands the power of “blue pali” and “red pali.”

So really, the contemporary passport serves two main functions: it confirms your national identity, and it is a travel document.

There is power in both.

The first function is pretty straight-forward. A money green passport says you’re Dupe, Oghene, or Salisu from Nigeria. If it’s burgundy you might be from the United Kingdom. If it’s blue you could come from the United States, perhaps black for Mexico and India. I could go on.

This matters. In a world of unequal realities where the achievability of dreams changes as you cross borders, simply being from a certain place can be aspiration enough. Greater wealth, better healthcare, and better education all attach themselves to certain nationalities while being absent for others.

For large numbers of “third-world” citizens, simply holding a developed country passport means holding a reality available only in the wildest of dreams. It is literally holding hope.

The second function is a bit more technical. Aside from telling the world who you are, the passport’s major purpose lies in where it allows you to go. Where your passport allows you to go varies remarkably depending on where you’re from. Holding one passport might make you a member of the community of nations, a global citizen free to jet-set between foreign lands. Holding another is a liability – a guarantee of lengthy visa processing times, letters of invitation, and pleas for the “privilege” of spending hard-earned money abroad.

The rules that determine which passport can do what seem arbitrary. They perpetuate a narrative, and contribute to the stratification of nations into those that hold power in today’s world order and those that don’t. If you aren’t sure where your country stands in the world, just draw up a list of countries your passport can get you into, visa-free. If you’re from the United States or the UK, you can get into 147 countries visa free. If you’re from Nigeria, that number shrinks to 61 (padded heavily by ECOWAS and countries like Vanuatu and Micronesia). Iraq and Afghanistan are down at 38.

Maybe I’d feel better if passport policies were rooted in some deep statistical analysis. But they aren’t. The passport conveys nothing about character, criminal tendencies or financial stability. A Senegalese man carrying a Senegalese passport can only get into 57 countries. If he marries a French woman (and holds it together for the requisite four years), he receives a French passport and visa free access to pretty much any country in the world.

The man is the same. The character is the same (unless marriage really does change people). Only the paperwork – and thus the assumptions made about him – have changed.

The history of passports show that today’s travel policies aren’t very old. As recently as the turn of the 20th century, passports weren’t required to travel within Europe, as enforcement was seen as difficult due to expansion of rail travel. With World War I came the need for enhanced border security, and more attention to the passport.

Sometime over the following 80 years, “security” somehow seemed to break the traveler community conveniently into developed, emerging, and third world countries, with that last group firmly on the outside looking in. As a country’s global standing (or, sometimes, harmlessness) grows, so does the list of countries its citizens can travel to visa free.

Putting metrics to the effect of travel policies on holders of restricted passports isn’t straightforward. How does one tally social currency? Can you put a figure on when, as a teenager, you’re weren’t allowed to sit with the “cool” kids at lunch? This isn’t about data. This is far more personal.

One of Lagos’ hottest young producers/presenters/hosts (and a good friend of mine), recently visited Los Angeles to participate in a three week long training program on production and self-representation. We discussed the opportunities the course would open up for her and other professionals attending. We discussed her hopes for the sort of networking that might result in a phone call with a gig, often at short notice. We discussed the fact that she arrived on her British passport, not her Nigerian one.

If she gets a call, she can be in LA in 48 hours, thanks to her British passport. “Things move so fast in this industry, I wouldn’t have a choice,” she said. And if she had only a Nigerian passport? “I don’t know. I don’t even know. I might as well not bother. I’d never make it in time.”

African athletes know the feeling all too well:

Last July, eight Nigerian athletes aiming to participate at the IAAF World Youth Championships in Colombia had their participation threatened by the rejection of their transit visa requests by Brazil. Forget permission to get into countries; some of us can’t even get permission to pass through countries to get to countries we already have permission to enter.

In 2013, top Eritrean cyclists were denied visas to Switzerland to train at the World Cycling Centre, despite their reputations in the sport, the invitation from the WCC, and the 1000km journey they had taken to Khartoum to apply.

In 2011, a youth baseball team from Uganda was stopped from being the first African team to play in the Little League World Series when their US visa requests were denied – “Issues” with the players’ ages, allegedly. In 2015 they finally made it, but it wasn’t easy. According to SBNation.com and Richard Stanley: “Parents or guardians had to sign documents, which meant 10-hour bus rides home for some kids. The regional tournament, meanwhile, was in Poland, which has no embassy in Uganda, so kids were bused to neighboring Kenya for visas.

Worse still, it’s becomes so acceptable to treat visitors from certain countries a certain way that even poor countries do it to each other: A Ugandan friend recently told me about her difficulty getting a visa to Guatemala for charity work. GUATEMALA! No offense, but no one is sneaking in to Guatemala to overstay. Ugandans are not threatening Guatemala’s security.

There isn’t a single serious reason anyone can give me for Ugandans having to navigate a bothersome visa process in Guatemala, while US and Mexican citizens (and potential drug-lords from those countries) can walk right in.

I’ll assume that Guatemala hasn’t had a considerable number of negative experiences with Ugandans. It’s more likely because few other countries let Ugandan passport-holders in visa-free. Guatemala is simply copying popular passport policy: people carrying a certain color passport can enter your country without scrutiny; others require a letter of invitation. It’s like how everyone started wearing those ridiculous long shirts because Kanye did, even though we all know they make no sense.

Travel policy has nothing to do with what nations think of you personally, and everything to do with what they think of your nation. Your passport embodies whatever reductive mythical or diabolical perceptions the world holds of your country, even if those perceptions aren’t based on experience.

People buy German because “German” equals “reliable”. They sound British because “British” equals “sophisticated.” They shop French because “French” equals “fashionable.” They lock out Syrians because “Syria” equals “Isis.”

People act on who and what they think you are, not necessarily who and what you actually are. In the absence of experience, perception is the go-to input, and where a passport allows its holders to go is as clear a reflection of perception as pretty much anything else.

The net cause AND effect of a weak passport is a perception of weakness. It is sitting away from the cool kids table. It is a reflection of a country’s place in global power dynamics, and right now, a lot of African countries look pretty powerless. If your athletes can’t even attend a sporting event for which they are well qualified, you can’t claim a real place in the global order.

I can’t give you a precise figure for what simply holding a Nigerian or Kenyan passport costs, but I can guess, based on where our passports allow us to go, that it costs a lot in terms of willingness to invest in-and experience our countries. It costs the “powerful” countries too. How much of the “Africa Rising” opportunity are they missing by not allowing witnesses of the story to more easily come to them?

The good news is there is room for negotiation.

From the Nigerian point of view, this new administration’s first year presents an unenviable to-do list. Power, water, education, security, etc. are all challenges requiring attention. But with a full cabinet in place, and the world giving Africa a new look for everything from successful democratic transitions to untapped investment opportunity, I can think of no better time for passport rights to be renegotiated.

Visa waiver programs are the brass rings of travel policy. The United States, for instance, extends its Visa Waiver Program (VWP) to 38 countries, mostly European, and all wealthy, friendly, and “stable.” The criteria for entry into the visa-waiver program are spelled out in the US code, and read like how you’d form your clique at a new school.

The first requirement is a non-immigrant refusal rate (the percent of non-immigrant visa applications that are rejected or refused) of under 3 percent. It’s almost counter-intuitive –if your visa approval rates are already under 3 percent, why the need for a visa waiver? Other requirements like “national security interest” pretty much guarantee that only countries “liked” by the US will make it into a VWP.

Fortunately, the US is only one country, and there is plenty of room for improvement elsewhere. I have no doubt that the bright minds in Africa’s various Foreign Ministries are capable of constructing similar programs.

For starters, within Africa itself, there is no reason a VWP couldn’t be established, eventually with extensions to popular tourist destinations like the UAE and countries in Latin America (where, conveniently, over-stayers would stick out like sore thumbs). Criteria needn’t be overly complicated:

- A record of legal round-trip travel for a given percentage of travelers from a certain country (as opposed to successful visa application rate)

- Proof of financial capacity to support the indicated intent for travel

- Comparable levels of wealth and stability between the two countries

- Established trade or cultural relationship between the two countries

This should open up visa-free travel between countries like Nigeria, Egypt, Kenya, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia, and South Africa, and popular international destinations in the Middle East.

The general thought is that if travel policy is built on subjective judgments of wealth, development, stability, and alignment, there is no reason those judgments can’t be negotiated, influenced, and reset. If African countries want to be seen as having a role in the global order, we need to walk and travel in that same swagger, providing our citizens the same access and privileges afforded to citizens of other countries. I’d put money on reality soon imitating perception.

A careless reading might leave the impression that I’m advocating open access for all. Not so. With the world on fire all around us, it has perhaps never been more important to have greater control and understanding of the people who travel into and out of our homelands. But this goes exactly to the opinions expressed.

A blanket policy for entire countries, based on their passports, is backward. As recent world events have shown, where French and Belgian citizens wreaked havoc in attacks on French soil, simply having a French or Belgian passport guarantees nothing about an individual’s intentions or character.

In other words, subjecting Abdulaziz to one policy when he carries an Algerian passport and another policy when he carries an American one is at best incomplete reasoning, and at worst dangerously careless.

Changes to those policies would only be the beginning. In an era of the cloud and big data, in which nearly everyone has parse-able travel, education, and financial records, blanket international travel passport policy – even with freer travel – is ineffective. It subsumes the rights and characteristics of individuals with treatment meted out for an entire group, violating several rules of basic human decency in the process. It punishes well-meaning travelers and rewards others for unearned circumstance, all based on where they’re from.

It’s lazy diplomacy. It’s costing us. And it has to stop.