On a Wednesday night in May 2017, Ade was on her way home from a ‘back of house’ event that ended pretty late when she was attacked and raped by a group of men. “The road to my house is a lonely path. I often take a bike but it was so late, there were no bikes so I had to walk,” she tells me. She walked past four men chatting, soon after, she felt something hit her from behind, “They dragged me to a place and raped me,” she says. “I went home and cleaned myself up. I didn’t tell anyone, not my sister, not her husband, no one.”

But something shifted in her. She became aggressive, particularly towards men, and her boss at the time noticed. Concerned, he called her into his office one day to ask what the matter was. She “opened up to him”, after which, he put her in contact with a gynaecologist who examined and treated her.

Post treatment, the gynaecologist asked Ade if she had heard of the organisation, Stand To End Rape (STER). “I said no. And he said he was going to reach out to them to get in touch with me.” A day after her meeting with the gynaecologist, a counsellor from STER reached out to Ade to ask if she’d like to undergo therapy with them, she said “yes” but that she’d prefer to do it over the phone. That marked the beginning of a three-week over-the-phone therapy session with STER.

STER is a youth-led non-governmental organisation that advocates against sexual violence and works directly with survivors of sexual and gender abuse, providing them with psychosocial support. Five years ago, Ayodeji Osowobi, founder and executive director of STER, established the organization in response to what she describes as a gap in sexual violence prevention and response in Nigeria.

“There were just pockets of organisations in specific places providing very specific support to people. I realised there was a huge gap because the services that were available were not commensurate with the number of people who have experienced sexual violence,” Osowobi says.

But even with these few organisations in place, a prevailing culture of silence facilitated by victim-blaming, shaming, and scepticism meant that sexual assault victims rarely spoke up or came forward to seek help. STER has helped to address that, in a way.

One thing the organization has succeeded at is creating an active and engaging social media presence that galvanises people to share their stories of sexual assault and report cases to them directly. STER often responds swiftly with an intake form that requests primary answers regarding a case. The intake form helps STER to understand what intervention is required, the survivor’s location, and the best way to reach them.

Offline, STER representatives go into communities to sensitise people on rape, sexual violence and assault and then collate data from affected persons. “The first step in dealing with a case is data collection, it helps us to understand where, when, and how we can help you,” Osowobi says. STER recorded 173 cases via its intake form last year.

Depending on the case, STER helps to provide medical support by referring survivors to organisations like the Women at Risk International Foundation or the Mirabel centre. Both are non-profit sexual assault referral centres based in Lagos. For cases outside Lagos, STER representatives accompany survivors to a public healthcare centre to be examined, tested, and treated. The organization covers the cost of the expenses.

Post-medical care, survivors are either accompanied to a police station to report their case or they go and make the report themselves, depending on what they’re comfortable with. If the survivor is willing to press charges, STER advocates for the prosecution of the case and provides legal assistance. Last year, STER provided legal support for 55 cases of sexual violence reported to them. “Once that is done, and the legal process is in motion, we then commence mental health therapy because we believe that therapy is important for every survivor to deal with their situation,” Osowobi explains.

Ade says the beginning phase of therapy was “tough”. According to her, her counsellor made her do things she wasn’t comfortable with, including writing a letter to herself and affirming certain mantras daily. “She asked me to forgive myself because I blamed myself for being in that situation, I blamed myself for being out that late. It was tough to do these things initially, but when I did them, they helped,” she says.

In the period that she underwent therapy, Ade was thinking a lot, had consistent panic attacks and struggled to keep her emotions in check. She avoided being in contact with people as much as she could, her therapy sessions with the counsellor from STER were the only other consistent thing in her life, besides the panic attacks.

When I asked what she thinks life would have been like for her had the three weeks of therapy not happened, she chuckles and says, “Well, I would have committed suicide.” Two weeks after she was raped, Ade lost her brother-in-law, the man, whose home she lived in. “We were quite close,” she says. She was experiencing double trauma and was deeply depressed. The daily over-the-phone therapy sessions with a stranger she had never met, saved her life.

While STER does not directly manage the medical aspect of sexual violence, the Women at Risk International Foundation does. Commonly known as WARIF, the organisation has a standalone health facility that offers immediate medical attention including forensic medical examinations and operations to rape victims. WARIF also offers laboratory tests for sexually transmitted diseases and administer post-HIV and post-pregnancy drugs within a 72-hour window.

As a public healthcare worker in Lagos years ago, Dr. Kemi Dasilva-Ibru, founder of WARIF, was often exposed to women who had endured tremendous acts violence. And so she started to help these women in her capacity as an obstetrician and gynaecologist by offering her services to sexual assault referral organizations and facilities pro bono for over seven years.

In the course of offering these services, Dr. Dasilva tended to two cases of child rape that moved her to establish WARIF in November 2016. One was the case of a two-year-old that had been raped by her father. And the other was the case of an 11-year-old that had consistently been raped by her aunt’s husband for years. Upon a closer look at the latter case, Dr. Dasilva realised that the little girl was in her third trimester and had no idea she was pregnant.

“So that to me was pretty much the line in the sand appreciating that I needed to now offer more structured care to survivors of sexual and gender-based violence. And for me to do that, I needed a vehicle. This is why I established the Women at Risk International Foundation,” she tells me. In the last three years, WARIF has attended to over 1100 girls.

During her time working in public healthcare, Dr. Dasilva also observed that healthcare workers lacked the necessary sensitivity training required to handle cases of sexual violence. “You would find the average girl or woman being asked to tell her story in an open space overheard by others. And in terms of the assistance received, these women would only get their medical needs attended to, nothing more,” she explains.

So in setting up her foundation, Dr. Dasilva put in place a 24-hour confidential helpline as a first point of contact to survivors of sexual violence who cannot physically reach the centre or those who simply want the anonymity of calling. In the last two years, over 630 calls have been received on the helpline, according to data provided by the organization.

WARIF tackles sexual and gender-based violence through three core strategies; healthcare service, community outreach, and educational programmes. Community outreaches include what is described as the Gatekeepers Project. This project involves an annual training of 500 traditional birth attendants (TBAs) from selected rural and peri-urban communities on the signs and prevention of sexual and gender-based violence, equipping them with the necessary tools to address this issue in the communities where they serve.

In rural communities, TBAs or traditional midwives as they are commonly called, are well-respected figures. The nature of their work allows them to build trust and form close bonds with the women in their communities. They are therefore in the best position to connect survivors of sexual assault in rural areas to the services of organizations like WARIF.

These trained midwives often communicate with WARIF through direct calls, a dedicated WhatsApp group, or a special two-way SMS platform. WARIF puts these midwives on the platform having trained them to use simple buzzwords like “Abuse” or “R” for rape to report cases of sexual violence in their communities. “We would immediately with the use of the platform know who and where it’s from. So we can efficiently galvanize resources to go and visit her. This helps us see cases in real-time and to address them more efficiently,” Dr, Dasilva says.

Baba Abiye, a trained birth attendant in the Ikorodu local government of Lagos state says prior to WARIF’s intervention, cases of sexual violence in his community were neither addressed nor reported. “When a girl or a woman is raped in my community, we often look away. But WARIF came in and taught us that sexual assault is a crime and that perpetrators can be dealt with,” he says.

He gave an instance of a case currently in prosecution, of a teenager that was gang-raped in his community. “I called WARIF, they came in and the matter was taken to the police. The perpetrators were arrested and taken to court. They are currently in jail while facing prosecution,” he tells me. Baba Abiye says cases of sexual assault has drastically reduced in his community since WARIFs intervention. “In my area, they call me “Baba WARIF”. They call me gbeborun(a snitch). They know that if they do anything wrong, it is my duty to inform WARIF immediately.”

In the last two years, WARIF has trained a thousand TBAs to be first responders of sexual and gender-based violence in rural and peri-urban communities. The Gatekeepers Project has seen about 500 active cases of sexual violence reported.

Unfortunately, organizations like STER and WARIF are held back by certain limitations, one of which is Nigeria’s criminal justice system. According to human rights lawyer, Omolara Oriye, the country’s criminal justice system is faulty and ill-equipped to handle cases of sexual violence. This, in part, is due to the prevalence of rape culture and bias in terms of the way society holds women to a higher standard of morality.

This bias is apparent in the way the police and healthcare workers manage rape cases by centring on survivors, with little to no attention paid to perpetrators. “When people like the police, doctors, nurses, and lab attendants who are supposed to prepare evidence cannot do that without bias, it affects the process and has far-reaching consequences,” says Omolara.

For example, survivors are made to recount their stories “five, six, eight, 10 times” by the police. This does not only cause re-traumatisation, it also affects the consistency of a story. Many times, these inconsistencies are held to be lies or discrepancies, and this hurts the case of a survivor. To address this problem, WARIF organises a law enforcement sensitisation programme, sponsored by the United States Agency for International Development(USAID) and the Aspire Coronation Trust (ACT) Foundation, to educate police officers on gender sensitivity and the right ways to engage a survivor. So far, over 690 police officers have been sensitized in Lagos state.

Olakunle Orebe, the inspector in charge of the gender desk unit, Lagos State, says the seminars organised by WARIF has helped to sharpen the investigative and interrogative skills of him and that of his colleagues in dealing with cases of sexual assault. “We are taught the protocols of handling and investigating sexual violence. For example, when we deal with survivors, we have to extract information from them carefully and sensitively. This is not common knowledge to all. So we are trained on how to handle such delicate cases,” he explains.

Another set back within the criminal justice system is the evidential requirement of corroboration to prove rape in court. Omolara says that in the last decade, many rape convictions were either dropped to attempted rape or perpetrators get off scot-free because of a lack of corroboration. “But rape doesn’t happen in public. People don’t invite an audience,” Omolara says. She also explains that other requirements like character evidence where the sexual history of the survivor is questioned, beats down the credibility of a survivor’s evidence and hinders conviction.

Because part of their work is largely dependent on collaborations and the efficiency of other agencies, STER and WARIF also have to deal with a lack of shelter to refer survivors of sexual violence. “There are times when I’ve reached out to a number of people and their shelters were full. Once, I tried to find a shelter for up to two months to place a client, but I couldn’t. At the time, I didn’t have enough money to help the client rent an apartment. So I feel like I failed that client,” Osowobi tells me.

However, as brilliant as these solutions are in tackling sexual violence, they all have one thing in common – they all are end-of-pipe, survivor-centred solutions. Hence in 2017, WARIF launched preventive initiatives to address sexual assault with the WARIF Educational School Program (WESP) and the WARIF Boys Conversation Cafe.

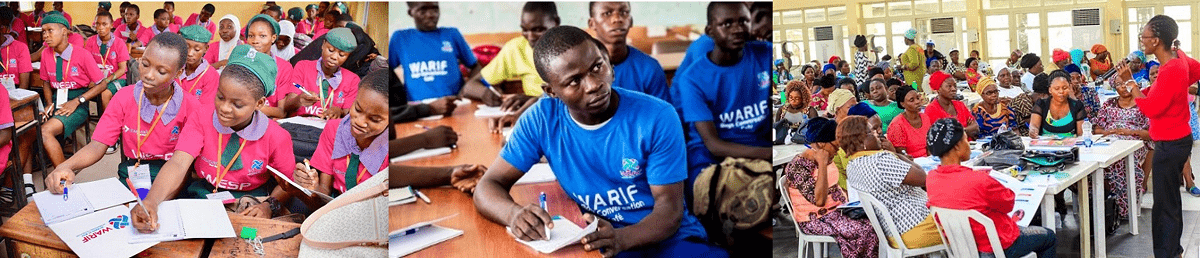

Both initiatives are a four-week school program targeted at teenage boys and girls, ages 12 to 16. The programs comprise weekly sessions from a specifically designed curriculum taught in schools by trained facilitators and mentors. Vetted role models from law enforcement agencies and other organizations go into colleges and have conversations on identifying guidelines and measuring the prevalence of sexual violence with young boys and girls.

“Our statistics will tell you that one in four girls has had one violent sexual encounter before the age of 18. And so we educate these young girls, giving them a simple toolkit of signs and prevention. And most importantly, give them the opportunity to seek our services when they need it,” Dr. Dasilva says.

The idea behind WESP and the Boys Conversation Cafe is to educate teenagers who have been socialized in abuse at such a young age that they do not recognise that they are in a sexually violent environment. The conversation cafe specifically address cases of sexual violence against boys as there are cases as high as one in eight in communities in Lagos State, according to Dr. Dasilva. Data report by WARIF indicates that 69 percent of cases attended to in over two years were minors between the ages of 0 to 18 years old.

A 2015 UNICEF report on ending violence against children in Nigeria states one in 10 boys has experienced sexual violence before the age of 18 in Nigeria. The report also documents low rates of disclosure and service seeking behaviour among boys and girls who have experienced sexual violence. 38 percent of girls and 27 percent of boys told someone about their experience. Of girls who experienced sexual violence, 16 percent knew where to seek help, five percent sought help, four percent got help. 39 percent of boys knew where to seek help, three percent sought help, two percent got help. Half the percentage of sexually abused boys said they did not seek help because they didn’t think it was a problem.

The impact of these educational programs by WARIF is cumulative; educating teenage boys and girls does not only change their attitude and behaviour towards sexual and gender-based violence, it also empowers them to become ambassadors who take whatever they learn back to other young boys and girls in their communities. A monitoring and evaluation exercise conducted to check the impact of the first four-week program held for teenage boys, recorded significant success in terms of immediate behavioural change in the participants; a 41 percent decrease in porn addiction, an 85 percent agreement on the importance of consent, and a 98 percent commitment to be active bystanders in any case of sexual abuse.

Another organization filling the gap for precautionary solutions against sexual assault in Nigeria is The Consent Workshop (TCW), a youth-led grassroots movement based in Nigeria, Canada, and St Vincent and The Grenadines. Borne out of a young woman’s social media activism to destroy rape culture, the organisation’s objective is precise – deconstruct rape culture through consent education, increased awareness on sexual violence, and the provision of resources.

In July 2018, Uche Umolu, founder and executive director of TCW, started a Twitter conversation that encouraged rape survivors to share their stories and expose their perpetrators. It was a huge success. So much so that people reported her account forcing Twitter to permanently suspend it.

Riding on that wave, Umolu started TCW the following month “so that the conversation doesn’t die on Twitter,” she says. And also because there’s a gap in terms of anti-rape solutions. “There’s a lot of conversations on rape and sexual assault now and a few sexual assault centres that offer support to survivors of sexual violence, but no one’s really focusing on preventive solutions,” Umolu tells me.

Her workshops, which she runs with the help of volunteers, take different structures and formats and are held in colleges, tertiary institutions, and communities across Nigeria. They generally comprise interactive sessions on sex, cultural attitudes towards sex, boundaries of consent, recognizing sexual violence, and the significance of active bystanding. Having these dialogues help youths unlearn harmful behaviours and make healthier sex-positive decisions, consequently upsetting rape culture.

So far, between March 2019 and April 2020, TCW has organised nine workshops within universities and taught consent education in six colleges across four states in Nigeria. But conducting these workshops can be quite difficult, particularly for a small organization; the nature of TCWs approach to tackling sexual violence and rape culture works against it in Nigeria. It’s easier for survivor-centred organizations like STER and WARIF to do their jobs because people typically go to them for help and support.

“Instead of people coming to us, we go to them asking that they let us in their doors,” Umolu says. “The school or institution has to want us there. A lot of the work we do requires collaboration with a second party in order for us to get into the spaces that we’d want conversations to happen.”

More often than not, schools, including universities, turn them away. Sometimes reneging on agreements or withdrawing invitations to have TCW in their spaces. Umolu blames this problem on (faux)conservatism; Nigerians typically shy away from conversations about sex. It is a taboo subject hence schools do not have a sex-ed curriculum and would not allow anything close to it within their establishment.

To tackle this problem at the tertiary level, TCW is collaborating with student bodies in universities to develop chapters within the institution. So far, there is a TCW chapter in some of Nigeria’s foremost universities including UNILAG, OAU, and Babcock.

Another obstacle to the organisation’s work is how institutionalised rape culture is in Nigeria. Teaching young men and women consent is great. But what happens when these young men and women are sexually assaulted by people in a position of power? For example, what happens when a lecturer solicits sex from a student in exchange for grades?

“There’s only so much I can do to tackle that problem. I can’t teach lecturers or professors about consent. For them, the issue is not consent, it’s power, and using that to gain whatever they want. So it’s very complicated when you’re dealing with an issue but what you’re dealing with is so systemic,” says Umolu.

There is also the general problem of a lack of data. There are no verified domains to get authentic statistics on the rate of sexual violence in the country or the number of convicted cases. Anti-rape and sexual assault organizations independently collate data of cases handled. But federal and state law enforcement agencies have no data.

The UNICEF report on ending violence against children in Nigeria is the common reference for journalistic reports and conversations on rape and sexual violence in Nigeria. But that report was based on a 2014 survey. Why the lack of data? Perhaps as writer, Chuba Ezekwesili, suggests, “the answer to that question reveals the depravity of a society that tacitly pressures rape victims into silence.”

“We don’t even have data to monitor how close we are to achieving sustainable development goal 5 (gender equality and empowerment for all women and girls). We often have to ask CSO’s across the board for their data. It is difficult working without data,” laments Osowobi. “Data helps you frame policies and programmes. If you don’t have data, you are only test running ideas.

Thankfully, last November, the Nigerian government finally launched a National Sex Offenders Register after years of anti-sexual assault organisations clamouring for one. This will serve as a database for convicted sex offenders and prosecuted cases of sexual violence. But as much as this is a step in the right direction, there is a host of issues that need to be fixed for the sex offenders register to be effective. “The law, the judicial process, the police force… The entire system needs reforming. It’s extremely difficult to be productive when the system is actively working against you,” says Umolu of TCW.

Note

- The name of the survivor was changed to protect her identity in this story.

- Some of the subjects interviewed were recommended by STER and WARIF.

- Most of the data present in the article were provided by the organizations discussed.