Today marks the 23rd year we are remembering the victims of one of the darkest hours in human history: The Rwandan Genocide. This day in 1994, a private plane conveying President Juvenal Habyarimana of Rwanda and President Cyprien Ntaryamira of Burundi was shot down close to the Kigali International Airport by a group that remains unknown. The event was the much-needed spark the Hutu majority needed to descend on their Tutsi countrymen. Within hours of the incident, the Prime Minister, Agathe Uwilingiyimana, a moderate Hutu was murdered, and from then it was blood, blood everywhere for the next 100 days.

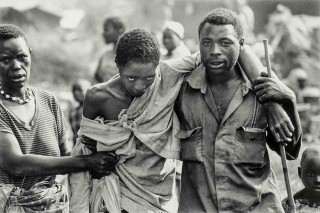

In what has now come be known as the Rwandan Genocide, the whole world watched on as about one million Tutsis, moderate Hutus and some foreigners were murdered at the hands of the Hutus who sought out their victims and eliminated them. Churches and sanctuaries became mortuaries. Priests became both assassins and undertakers. There was no sacred place. The plan was to spare no one and no one would have been spared if not for the bravery of a few good Rwandans who took it upon themselves, using every means available to protect as many people from the marauding murderers. As much as we remember the victims of the genocide, we should also remember to celebrate those who not only remained good in the face of evil but also went out of their way to protect people ─ some paying the ultimate price along the way.

Sadly, as profound as this dark history has been in these past 23 years, a good number of the heroes of the genocide have been forgotten; only a few have been recognised. Paul Rusesabagina, whose heroic deed was portrayed in the 2004 movie, Hotel Rwanda, is a common name among the heroes of the time. Paul Rusesabagina, 40 years old at that time, was the manager of a five-star Hotel de mill Collins in Kigali in the genocide. He was a man who took it upon himself to save so many lives, using his wealth and connections. Even though the accounts of his heroism are still very much contested following the award of Lantos Human Rights prize to him in 2011, no one can dispute the fact that he saved lives in a sheer act of modern heroism.

But it was not just Rusesabagina who used all he had to save people during those dark days. There are others. Captain Mbaye was one of the people that paid the ultimate price while saving others. As we remember the victims today, the heroes (we have named three) deserve to be remembered and celebrated.

Captain Mbaye Diagne

“When you put everything he did together, it becomes clear that this was one of the great moral acts of our times.”

Much has been said about the inactions of the UN and the complicity of some peacekeepers during the 100 days siege in 1994, there is, however, one man that defied orders and mission agenda to heed the call of humanity as he saved over 50 people during the genocide.

The story of this once in a lifetime hero was told by a man who worked with him, Mark Doyle.

From accepting to transport the five children of Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana who was murdered within the first few hours of the genocide to the Hotel Del Mill Collins which was serving as the safe house of the UN, to walking in at the right time to prevent a Hutu priest from murdering a Tutsi woman who was taking refuge at the church, the timing of Captain Mbaye was impeccable.

No other expression better describes the effect of his presence at the Sainte Famille Church than these words from Mark Doyle, “There was no large-scale killing inside the Sainte Famille compound, partly as a result of the efforts of Mbaye and the other UN peacekeepers – although plenty took place just outside.”

He was an ordinary unarmed military observer reporting to the UN peacekeeping mission, but he did the job of a man with an extra life. Through roadblocks and bullet teeth, Mbaye transported endangered Tutsis and Hutus while the rest of the UN soldiers were torn between their humanity and sticking with their mission agenda. At the end of the day, even if they wanted to follow their humanity, they were under equipped. But it never mattered to Captain Mbaye, a northern Senegalese man in his mid-30s who was built, gap-toothed and funny. His weapon was his laughter, which he deployed in buying the conscience and his way through the Hutu militias as well as delivering momentary joy to the distressed Tutsis.

The journalist who put out his story after 20 years was himself saved by Mbaye through one of his jokes. However, though the joke was his most obvious and readily available “weapon”, he did not rely on just his jokes. He used cash, alcoholic drinks and cigarettes which are forbidden by his religion, Islam, to buy his way. He used all he had, not sparing his life, as a means to an end to save as many people.

As Captain Mbaye was driving through deathly hallows to take people to the Hotel de mill Collins safe house, Paul Rusesabagina was doing all he could at the hotel to keep them well fed and secured. Their successful protection of over a thousand people was down to the collaboration between Rusesabagina and Captain Mbaye, as well as some UN peacekeepers.

What underlines his heroism is the fact that he was acting all alone to save people, in clear defiance of the agenda of the UN peacekeeping mission. It, however, was not long before his actions got to the notice of the majors in the army. Surprisingly, recognising the service to humanity Mbaye was carrying out all by himself, rather than reprimand him for breaking orders, General Romeo Dallaire, the head of the mission corroborated the efforts of Mbaye which resulted in over a thousand escaping the onslaught.

He, in the company of some other UN officials, at some point organised convoys to take some people in the hotel to the airport where they had prepared jets to transfer them out of the country. And the plan would have been successful but for a Hutu worker at the hotel who leaked the plans and names of people on board to a Hutu radio. The radio went ahead to read out the names of the Hutu on the vehicle, inciting the Interahamwe against the UN convoys. Seeing the preparedness of the militia to kill them, Mbaye reportedly stepped out of the vehicle onto the road while shouting “These people are my responsibility, you would have to kill me first before you kill them.”

Even though they had to return to the hotel, Mbaye saved lives that day. His luck, however, ran out on May 31, 1994, when a bomb went off a few metres away from his car while on an errand to deliver a message to an army major in the rebel-controlled area of Kigali. A shrapnel tore through his flesh and he died immediately, paying the ultimate price of service.

Captain Mbaye remains one of the greatest heroes of the Rwandan genocide. His love for humanity was beyond military orders. But he lost his life in the process of gaining lives. His acts capture the essence of humanity. There is no better gospel in the 21st century.

Jean-Francois Gisimba and Carl Wilkens

Another less pronounced hero of the Rwandan Genocide was Carl Wilkens, a humanitarian and aid worker who had only moved his young family to Rwanda in 1990, four years before the genocide broke out in 1994. When the killings started in April 1994, Carl and the rest of the foreigners were asked to return to their homes countries. Carl, however, refused to leave Rwanda, daily venturing into the streets through bloodthirsty soldiers taking food and water to people. He probably didn’t realise he was the only American left in Rwanda after all others had left immediately the genocide started. Friends and the United State government couldn’t convince him to leave. He stayed back to help as many survive by getting food and aid to people trapped in different part of Rwanda, especially Kigali.

It was Carl who later saved over 400 people with nothing but his presence at a time when the world had literally left Rwandans to die at the hands of their brothers.

He had heard of an orphanage home in Kigali with people who were starving to death. All he wanted to do was get them water and other needs. He went there first to see the place, see the people, see how much needs he would be bringing, but unbeknownst to him, he walked in at a time the Interahamwe had planned to murder every Tutsi hiding away at the orphanage. They had killed eight the previous day.

As the head of the orphanage, Jean-Francois Gisimba, was pleading him to wait and witness the massacre that would soon occur so that their story could be known to the world, the Interahamwe had started surrounding the building. But on sighting the American, the leader asked them to halt and not carry out the massacre before him.

“We were going to carry out our mission, but the American is there.’ The boss said in Kinyarwanda: ‘Leave the place, don’t do it in front of that man.”

Seeing the massacre that was to occur, Carl ran to the office of a key militia figure whom he had previously negotiated the supply of food and water to the orphanage with. It was there he met Prime Minister Jean Kambanda who promised nothing would happen to them. That effort bought the people 72 extra hours to live. The Interahamwe, however, returned three days later, fortunately, not with the intent to kill. The people were rescued and by another 72 hours, the rebel militia had reached their abode.

He saved the lives of over 500 people without raising a weapon.

Zula, born 1925, is a woman, a war hero who saved as many as 100 Tutsis, 50 Hutus and 20 Twas during the genocide. She did all this in an unusual way: through sorcery. She had prepared for their coming in earnest. She had dipped her hands in a herb that causes skin irritation while patiently expecting the killers. It was not long before they came. When she was asked to produce the Tutsis she was hiding, she denied ever setting her eyes on one, threatening them to vacate her compound or die. As the altercation ensued, she proceeded to touch some of the soldiers who believed she was cursing them. They retreated at first, then resorted to shooting through the walls. As Zula was trying to save over a hundred people she hid in her small house, one of the bullets caught her first son, and he died immediately. Days later, her daughter was poisoned. But all those didn’t matter to Zula even in the face of mockery.

It was not the first time Zula’s unconventional means would save lives. As she narrated, she saved the life of the current Rwandan president Paul Kagame as a kid during an earlier ethnic clash in 1957. Zula had asked Kagame’s mother to use her, Zula’s, bead in disguising Kagame as a girl as Hutu militias were then looking out for Tutsi boys. She recollected that she prophesied that day that if Kagame lived through the slaughter, he would come back to lead his people.

Even though witchcraft is now redundant and unpopular in a much developed Rwanda, it is this ancient tradition Zula used in saving as many people as she could. It is this unconventional means that has fetched her global recognition and several awards for heroism.

In all, these heroes, largely unsung, altogether saved about 5,000 lives, putting theirs on the line, not minding the challenges as though there were none, and laughing through obstacles like it as a pastime. They graciously saved the people the world, the United Nations and the trusted soldiers neglected out of passion that was spontaneous and lifesaving.

At a time when people living in war-torn zones are suspicious of one another rather than caring for and helping people out, these heroes could be a beacon of hope for each one of us. In these people, we find the very reason for humanity, our purpose of existence.