In 1972, the Israeli Air Force resettled an African population under threat of extinction in the Holy Land, where its ancestors were thought to have lived thousands of years earlier. Today some young African-Israelis are speaking out about this little-known mission and wondering why the state didn’t facilitate their own immigration to the country until over a decade later.

SEPTEMBER 1972: Prior to the operation, Israeli Air Force Brigadier General Joshua Shani had received only sparse data about the mysterious East African rendezvous point. Shani did not know if the secluded clearing – remote even for Ethiopia – would be long enough and tough enough to land on. As he steered the plane towards the isolated site, he observed that the pre-ordained patch had already been used as a runway, but certainly not in the recent past.

Shani managed to land his Hercules Stratocruiser without any complications, and soon after he touched down, a convoy of trucks rolled into the expanse, carrying their precious cargo. Under the watchful eye of a bespectacled Israeli university professor, twelve wooden crates were taken off the trucks and manually loaded into the plane’s cargo hold. Once all the freight was safely on board, Shani revved up the engines in preparation for take-off and the return flight back to Israel.

Above the roar of the plane’s engines, Shani could now hear hysteria emanating from the cargo hold. Inside each wooden crate was a living, breathing, bleating donkey. More than this, they were undomesticated donkeys, unaccustomed to either man or machine, to say nothing of being swallowed whole by a huge metal tube capable of flight.

After a short jaunt down to Djibouti to fill up on fuel, Shani ferried the unassuming animals to Israel. Landing at the brand new Etzion Air Force Base in the Sinai Peninsula – territory Israel had recently won in war – Shani was greeted by a delegation of dignitaries, including the mayor of the nearby city of Eilat. Once the animals disembarked, Shani took off again for Ben Gurion Airport, his role in this mission fulfilled. “Except for the smell, there was nothing left in the airplane,” says Shani.

Over four decades have passed since Shani brought the donkeys to Israel. His thick mane of black wavy hair has since turned silver grey, and he now wears prescription lenses to correct the once-perfect vision in his coffee-colored eyes. But his healthy skin and his fluid gait give off the impression of a man significantly younger than his seventy years. He still recalls carrying out Mivtza Arod, or as it translates to English, Operation African Wild Ass.

But ferrying a dozen livestock to Israel in 1972 only merits a mere footnote in Shani’s autobiography. The most illustrious operation of his military career took place four years later with another foray into East Africa. In 1976, Shani was the lead pilot of Operation Thunderbolt, a daring mission to secretly transport Israel Defense Forces commandos to Uganda, rescue over a hundred hostages held at Entebbe Airport by plane hijackers, and return to Israel.

Shani retired from active service a quarter-century ago. Like many ex-IAF officials, he has made a smooth transition from the Israeli military to the private sector. He currently serves as Chief Executive Officer of the Israeli subsidiary of American aerospace and defense firm Lockheed Martin and he resides in the affluent town of Caesarea, where his fellow residents include Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Shani can still recall the day he was asked to transport a dozen donkeys from Ethiopia to Israel. “It was a little bit strange in the beginning, but then I said, ‘Why not?’ It’s like a national mission to revive the animal wildlife that were existing in this country in the past,” says Shani. The impetus behind the operation, Shani explains, was two-fold: to preserve a community of animals that was in serious danger of going extinct; and to populate the land with animals that were written about in the Bible, but which had since disappeared.

After arriving in Israel, the wild asses were taken to the nascent nature reserve ‘Hai Bar’, about thirty kilometers north of Etzion Air Base, to live out the rest of their lives. Hai Bar opened its gates to the general public exactly five years later, in September 1977. “It was a nice mission,” Shani says upon reflection. “And I did go with my family to see the animals a few months after that. And let me tell you, it was an exciting thing to see them running in the desert of Eilat.”

“Wildlife of the Land of the Bible”

Shani was the man who physically brought the donkeys to Israel, but the mastermind behind the operation was the late pioneering Israeli ecologist and Hai Bar founder Uri Tson. In his 1990 book “A Dream That Came True: Wildlife of the Land of the Bible,” Tson recalls the thoughts and feelings that motivated him to establish Israel’s first wildlife reserve.

“In 1953, when I acquired books by researchers… about rare animals from the Bible that are going extinct in Israel and around the world, I was inspired. I felt a huge push, I know I had to do something immediately. I decided that we must act to save and preserve them as quickly as possible, before it will be too late!”

A decade later, in 1963, Tson secured the support of the Israeli government, and the Hai Bar nature reserve was established in the Arava desert, just south of Kibbutz Yotvata. At first, Israeli zoos transferred some of their animals to the Hai Bar, but the harsh climate of the Arava proved unbearable for them, and by the end of 1969 they had all perished from the dry desert heat.

Then, by sheer chance, the possibility of reviving the Hai Bar presented itself. In 1972, in a meeting with the director of an American zoo, Tson’s colleague retired Major-General (and later Likud Member of Knesset) Avraham Yoffe learned that an Italian merchant of exotic animals had spotted a flock of a dozen African wild asses in the Danikil Desert of Ethiopia. At the time, U.S. law forbade the purchase of African animals, but Israelis were under no such restrictions.

Tson had already identified the African Wild Ass as one of the species he intended to reintroduce to the Land of Israel. Determined to take advantage of this rare opportunity, Tson immediately sent Hebrew University Department of Zoology head Heinrich Mendelssohn to Ethiopia in order to verify the identity of the animals. Mendelssohn confirmed that the asses were authentic, and a deal was struck.

Working with a window of only a week to ten days, Tson set out to acquire everything he would need to relocate the asses to the Arava. From the Druze village of Daliyat al-Carmel, he hired an expert construction crew to build an enclosure that would hold the asses upon their arrival. From the government, he acquired the necessary funds to purchase the animals and pay off the requisite Ethiopian officials. The total price tag was $90,000, over half a million dollars by today’s standards.

And to fly to Ethiopia and back with twelve wild asses in tow – a cargo weighing six metric tonnes in total – Tson enlisted the Israeli Air Force. He had met then-IAF Commander Moti Hod at a Hai Bar fundraising event two years earlier, and Hod had volunteered that he would be willing to put a small plane at the disposal of the Hai Bar, if Tson could make decent use of it. In 1972, Tson called in the favour and asked Hod to make good on his offer. Hod agreed to Tson’s request and ordered Shani to pilot the mission.

The Ingathering of the Exiles

The African Wild Ass is considered to be the ancestor of the domesticated donkey. Its appearance is similar to the donkey that modern humans have come to know, except for the dark brown horizontal stripes on its ankles. By the 1970’s, only a few hundred African Wild Asses were believed to be in existence. But Tson sought them out, because they were mentioned in the Old Testament, in the Book of Job:

“Who has let the wild asses go free? And who broke their chains? I have given them a home in uninhabited places and tents in the land of the salt waste. He scorns the multitudes of the city, he hears not the shouts of the driver. He ranges the mountains for his pasture and he searches eagerly for green grass.”

– Job 39:5-8

Inclusion in the Biblical text elevated the importance of the wild asses for Jewish Israelis, and for the Zionist migrants that preceded them.

Beginning in the late 19th century, practitioners of the Jewish religion and their secular descendants began to immigrate to the Land of Israel – then the province of Palestine, part of Turkey’s Ottoman Empire – in noticeable numbers. Zionist thought held that Jewish people would continue to face racial and religious hatred, no matter where in the world they lived, until they constituted a majority in a nation-state of their own.

Several countries were considered for colonization, but Palestine was chosen because it was the land where the stories of the Torah took place. Ironically, many early Zionists did not practice religious lifestyles and considered themselves to be secular citizens. Nevertheless, they held that the Bible was important, because it contained a promise from Yahweh – God – to grant the Land of Israel to the Jewish people in perpetuity.

When Zionists arrived in Palestine in the late 1800’s, Jewish people only constituted a small minority of the population; most of the locals were either Muslims and Christians. Some of the Zionist immigrants were content to live in the land as equals and ethnic minorities. But others plotted to facilitate massive Jewish immigration and eventually outnumber the Muslims and Christians, to turn Palestine into Israel, a Jewish State.

When local Palestinians realized that some Jews had immigrated to the country with the intention of taking it over, some resisted these plans violently. Zionists soon acquired weapons in order to fend off these attacks and in order to instigate reprisal attacks of their own. Without a hold on the reigns of power or the sheer force of numbers, Zionists needed to supplement their military might with discrete diplomacy and publicity campaigns.

In 1947, the General Assembly of the newly-formed United Nations voted to partition Palestine into three territories: an Arab state, a Jewish state, and an international protectorate in the holy city of Jerusalem. War ensued, and Jewish leaders declared the State of Israel into existence, on the territory apportioned to Jews and on lands their militias captured by force from the other two proposed entities. Twenty years later, the Israeli army captured the other two territories, completing its conquest of historic Palestine.

During the 1947-8 war, Zionist forces drove out approximately three-quarters of a million Palestinian Arabs and refused to let them return when the war was over. The new Israeli government then confiscated their lands, declaring them to be the property of the state. For the next two decades, Palestinian Arabs in Israel were subject not to civil law, but to military rule. In 1966, their status was ostensibly upgraded to regular citizenship, but it remains inferior to Jewish citizenship in a number of critical ways.

The following year, Israel captured the rest of historic Palestine and put the Palestinian population there under its rule, as well. Fifty years have since passed, and these West Bank Palestinians continue to be governed by Israeli military law to this day. Under these circumstances, in which the Israeli government treats Palestinian people unequally on their own land, the legitimacy of the Zionist political project continues to come under challenge.

In response to these challenges which have not abated over time, some Zionists hope to firm up international support for Israel by playing up Palestine’s Biblical history, in an attempt to appeal to American evangelicals. Uri Tson was one of these Zionists, and the Hai Bar was one of these attempts to hype up Israel’s Biblical bona fides for the Christian crowd. Restoring the fauna that supposedly existed in the land in the time of the Bible would lend credence to Israel’s claim to be a reincarnation of a previously existing political entity, not a colonial regime that had displaced the natives – or so Tson had hoped.

Ethiopian-Israelis Allege State Racism

Palestinian people have historically been the chief victims of the Israeli state’s discriminatory policies. But another population inside of Israel has also complained of racist treatment by the government, and in recent months they have ignited street protests.

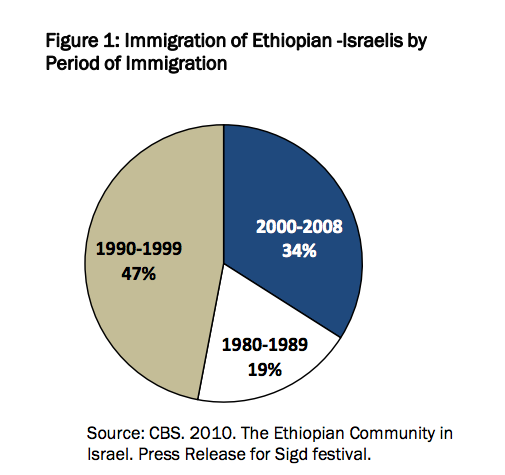

In April and May 2015, Ethiopian-Israeli Jews descended on downtown Tel Aviv and rallied outside the Jerusalem residence of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, protesting police brutality and state-sponsored racism against their community. The outpouring of anger was triggered by the release of a viral video which showed Israeli police officers beating an Ethiopian-Israeli soldier without any obvious just cause.

In truth, resentment had long been building up in the Ethiopian-Israeli community. For years, certain Israeli schools had refused to accept any Ethiopian-Israeli students. In early 2012, Israelis learned that an entire neighborhood in the town of Kiryat Malachi had conspired to ensure that no apartments in their block would be occupied by Ethiopian-Israelis.

Later that year, Ethiopian women accused a group working with the Israeli government of coaxing them to accept birth-control injections as a condition for being permitted to immigrate to Israel. Also, the consistent refusal by Israeli health service providers to accept blood donations from Ethiopian-Israelis has been a recurring irritant for the community.

But it was the frequent negative interactions between Israeli police officers and Ethiopian-Israeli citizens which finally brought the latter out into the streets in large numbers to protest the former. News of the Black Lives Matter protests which were occurring simultaneously in the United States further galvanized some Ethiopian-Israeli youth, who have begun to blame base racism for what they allege is the over-policing of their community.

Just as Israeli media outlets began to pay attention to the Ethiopians struggling in the streets, the executive director of the Israel Association for Ethiopian Jews elected to retrieve Operation African Wild Ass from the dustbin of history and raise the issue openly in a radio interview. The campaign to bring Ethiopian donkeys to Israel would have remained unknown to most Israelis – except to the scientific community and a few die-hard animal conservationists – were it not for IAEJ executive director Zeva Mekonen-Degu’s public comments.

That the government agreed to airlift Ethiopian donkeys to Israel over a decade before it was willing to airlift Ethiopian Jews is proof of state-sponsored racism, Mekonen-Degu alleged on air. “How are you supposed to react?” she blared out to the show’s host Keren Neubach. “To land a plane in some hole in Ethiopia, and to load it with donkeys, and to bring them here so animals of the Bible will live in Israel, while there are Jews there knocking at the door and saying, ‘We want to come! Our dream is to be in Israel, not in Ethiopia!’”

Mekonen-Degu’s on-air reveal marked the first time that Operation African Wild Ass had been mentioned in Israeli mainstream media in decades. But the story had not eluded the notice of Young Ethiopian Students, a collective of radical Ethiopian-Israeli bloggers. YES learned of the operation from the Israeli Air Force journal Bita’on, where an official account of the operation was published in August 2004. The activists exposed the story to their readership in a November 2011 blog, entitled “Jews from Ethiopia, NYET. Donkeys, DA.”

For years, the members of YES have steadfastly refused to give media interviews, preferring to let their work speak for itself. But when the most recent round of protests broke out, the group’s founder and editor Hananya Vanda agreed to speak to Ventures about anti-blackness in Israel. “Why did the Jews of Ethiopia arrive in Israel in the early 1980’s? Why did the massive immigration occur only at that time?” Vanda asks rhetorically. “Why, nevertheless were the Ethiopian Jews among the last to arrive here? It is of course based on race.”

Israel-Ethiopia Relations Were Close But Fragile

Hebrew University Professor Emeritus Haggai Erlich, a prolific author and prize-winning expert in Middle Eastern History, believes that it was not state racism but Israel’s geo-political interests that prevented it from facilitating the immigration of Ethiopian Jews before the mid-1980’s.

From the late 1950’s until the Yom Kippur War of 1973, relations between Israel and Ethiopia and Israel were especially warm, says Erlich. Ethiopia cherished these close connections, especially because of the Biblical brotherhood between the two peoples, sealed between the Israelite King Solomon and the Ethiopian Queen of Sheba. “If you read the Ethiopian newspaper, the Ethiopian Herald in English and Addis Zemen in Amharic, there were more articles on Israel than on all other countries in the world, combined! They were admiring Israel,” said Erlich.

For Israel’s part, its partnership with Ethiopia represented one of three vital alliances with non-Arab regional powers, perhaps even the most important of them (the other two were Turkey and Iran). As such, Israel invested considerable human resources in efforts to buttress the emperor’s rule and augment relations with him.

“From the Israeli point of view, that was a cornerstone, the strategic relations with Ethiopia,” said Erlich. “It was like an Israeli colony. There was a school in Hebrew for the children of the advisers and emissaries and experts – the best of Israel. There were one hundred families in Ethiopia, seventy in Addis Ababa. The best experts in whatever field, from education to medicine. Especially security, the army. In every battalion in the army, there were Israeli advisors.”

Although Ethiopia held Israel in high regard, and although it grew to depend on Israel’s military advisers and technology experts, Israeli diplomats were hesitant to actively promote Zionism among the Jews of Ethiopia, because Emperor Haile Selassie feared that any fracture in Ethiopia’s fragile multi-cultural mosaic could contribute to the country’s dissolution, says Erlich.

“Haile Selassie would say to the Israelis, ‘Look, I know that there are Jews here. You are invited to help them – but as Ethiopians. You help the whole neighborhood there, not only the Jews,’” said Erlich. “‘If I recognize them as having the right to depart from Ethiopia – half of my population is Muslim! They consider themselves Eritreans, Somalis. The Arab revolution around me, they all want to dismember Ethiopia. I cannot exclude the Jews.’”

“‘If you want to render them help, okay,’” says Erlich, paraphrasing the Ethiopian Emperor. “‘But don’t spread Zionism there, and don’t give them the illusion that they can leave.’”

Israeli influence in Ethiopia peaked in 1972, but it would not last. Muslim-majority African countries began to put pressure on Ethiopia to cut ties with Israel, and threatened to have the headquarters of the African Union removed from Addis Ababa if it did not do so. Inside the country, the pro-Israeli Viceroy of Eritrea (then an Ethiopian province) Leul Ras Aserate Kasa was losing leverage, while Arabia-oriented Prime Minister Aklilu Habte-Wold saw his clout increase.

Under these circumstances, Erlich says, Israel was hesitant to make any move that could threaten its crucial union with Ethiopia. “Every ambassador from Israel sent to Ethiopia was giving instructions to also make connections with the Beta Israel [Jews of Ethiopia]. Help them as much as you can, without jeopardizing the strategic relations, without too much giving them the illusion that tomorrow morning the State of Israel will come and lift them, like in [Operation] Magic Carpet, to Israel.”

Israel Delayed Immigration of Ethiopian Jews

Radical blogger Hananya Vanda says he is familiar with Erlich’s work and respects his research. Still, Vanda is convinced that successive Israeli governments chose not to facilitate the immigration of Ethiopian Jews until the mid-1980’s because of their black African identity – and that Operation African Wild Ass provides part of the proof.

“They brought donkeys – but they couldn’t bring Ethiopian Jews! Because it was dangerous. So this is the rhetoric that they tell us, in order to claim that the circumstances had not ripened to bring the Jews of Ethiopia – not because Israel did not want them here, but because the Ethiopians themselves were not willing to release them. That’s hogwash, of course.”

For most the second half of the second millennium of the common era, Ethiopia was effectively cut off from the rest of the world. Moreover, unlike Jews in other parts of the world, the Jews of Ethiopia lived rurally and did not play a central role in the nation’s affairs. When Western explorers of the 19th century began to report that they had met black Jews living in Ethiopia, they were met with obstinate disbelief.

“These Jewish features that we observe in this group, they are vestigial, they did not originate with the ancient Israelites, they are not archaic,” said Vanda, explaining the scientific consensus of the time. “Ethiopia itself has Jewish characteristics, and this group is a segment of society that preserved what had survived. They are a reflection of a Christian group, they do not have a real connection to Jews. In other words, they are not of the Jewish race, if there is such a thing as a Jewish race. Of course, there is none – it’s a social construct.”

As such, the first hurdle facing Ethiopian Jews who wanted to immigrate to Israel was proving to internationally-recognized religious authorities that they were, in fact, true Jews, and not Hebrew Christians. An official clerical proclamation proved elusive for decades.

“There are Questions and Answers by the [Egyptian sage] Ratbaz from the 16th century, who already says it. In the twentieth century, there is [Chief Rabbi] Rabbi Kook. In the 1950’s, there is [Chief Rabbi] Rabbi Herzog. But only [Chief Rabbi] Ovadia Yosef published it as a religious ruling.” said Israeli academic Dr. Chen Tannenbaum-Domanovitz, whose 2015 doctoral thesis focused on Israeli leaders’ correspondence on the topic of Ethiopian Jews.

Yosef finally declared in February 1973 that the Beta Israel were authentic Jews, but made their full acceptance conditional upon a conversion ceremony involving a ritual baptism, and for men, drawing blood from their penises, to symbolize a second circumcision.

Even after the 1973 ruling, Israeli authorities raised objections. “Then they said they needed the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi to say it, because Yosef was the Sephardi Chief Rabbi. And then the story goes that the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi said, ‘But Rabbi Kook already said it, so I don’t have to say it again.’ In the end, he also said it. And then there is the issue of it still taking another year and a half until the Law of Return is applied to them,” Tannenbaum-Domanovitz explained.

In the time it took Israel to agree to accept the Beta Israel as legitimate Jews who are eligible to immigrate, the state’s relations with Ethiopia had deteriorated inexorably. In October 1973, Egypt and Syria attacked Israel in an attempt to reconquer territory captured by Israel in 1967. While the three-week war was still ongoing, the Ethiopian Emperor cut off diplomatic relations with Jerusalem. Less than a year later, Selassie was deposed by his own soldiers and replaced by a Communist regime.

For eleven years between 1973 and 1984, the American Jews who advocated on behalf of their Ethiopian co-religionists were told by Israeli government officials that the Beta Israel could not be repatriated because of Jerusalem’s diplomatic divorce with Ethiopia.

“[Israeli officials] say, ‘There aren’t any diplomatic relations.’ So [American Jewish activists] tell them, ‘You don’t have any diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, either! And you’re bringing Jews out of there.’ That’s what they told them, all the time, explains Tannenbaum-Domanovitz. “What the [American Jews say] completely in the open, is: ‘If they were white, you would have brought them! There are no problems of diplomatic relations if they are white. If they are black, all of a sudden there are lots of problems.’”

Eventually, the Ethiopian Jews began to trek north on foot. As they languished in Sudanese refugee camps, Israeli officials postponed the airlift until the Beta Israel provided them with genaeological charts to prove their Jewish lineage. In the end, over four thousand Ethiopian Jews died as they waited for years for the Israeli government to retrieve them: from starvation, from diseases, and from murder.

According to Tannenbaum-Domanovitz, archived documents from this era reveal that Israeli diplomats and bureaucrats were reluctant to aid the Ethiopian Jews. “They don’t say ‘black’, but they always talk about primitive culture and that they will have to span a cultural gap and that they will be miserable and that it is preferable for them to stay in their ‘homeland,’” says Tannenbaum-Domanovitz. “We’re not sure they will be happy here, how will they manage, what will they do here. These are the things that they say.”

Today, the Ministry of Education teaches a very sanitized version of Ethiopian-Israeli history. According to Tanenbaum-Domanovitz, the new narrative is “we came and rescued the miserable Ethiopians and brought them over.” The battery of stumbling blocks foisted upon Israel’s only-ever group of Jewish immigrants with black skin is left out of the story.

“And then when they protest, one of the things people tell them is, ‘You should thank us for bringing you here.’”

Science Spoils the Zionist Narrative

That the Israeli government held up the immigration of Ethiopian Jews – even as it facilitated the immigration of Ethiopian asses – should trigger some serious soul-searching. But this revelation need not cast a pall over the efforts of Uri Tson and others to bring the undomesticated donkeys to Israel. It is not at all certain that they would have survived into the twenty-first century if they had been left to fend for themselves in the Danikil Desert.

In the four decades that followed Operation African Wild Ass, the descendants of those donkeys continued to live at the Hai Bar. Some of them were sold or traded to animal reserves in other parts of the world. But it turns out that none of them were released into the wild in Israel, as Hai Bar founder Uri Tson had originally intended.

“The professors and scientists talked about the animal called the African Wild Ass being here earlier. The hubbub was that it was in fact found in nature in Israel. That’s the reason that they brought it. That was the idea,” says Zohar Ben Shitrit, now manager of the Hai Bar. But experts later came to the conclusion that this was not the case. “No one has found any evidence for them in Israel, so they halted the program a long time ago and decided not to release them into the wild.”

Although undomesticated donkeys may have lived in the land in the time of the Torah and the Talmud, they would not have been the exact same species that has survived to the present day. Over time, animal communities adapt to their changing environments and experience genetic drift. “The whole idea of returning animals to the wild is for a limited period of time. They’re not talking about what existed thousands of years ago. Rather, which animals were here a hundred or two hundred years ago, let’s try to restore what existed here,” Ben Shitrit explained.

That the Israeli government approved a military operation to retrieve a dozen donkeys from East Africa which were later revealed to not even have a specific scientific value is a testament to the loose laws of engagement that existed in the early years of the state.

“In the past, there were no rules. The state had laws, but it was all fresh. Today, to do anything, you need a permit, consent, approval, government legislation. Back in the day, they came and said, ‘This once belonged here, let’s bring them!’” says Ben Shitrit. “You know how it is. This guy knows that guy, that guy knows this guy, let’s cut to the chase. That’s what they did.”

Although the wild asses strolling across the sandy flats of the Hai Bar enclosure are not genetically identical to the undomesticated donkeys that roamed the land in Biblical times, they are still a species that is in danger of becoming extinct. The preservation of this flock and other rare animals has since become the Hai Bar’s new raison d’être.

Today, Ben Shitrit looks back upon the tenacious efforts of Uri Tson in admiration. “It was the ideology of one person. A person who came and made his impact,” said Ben Shitrit. “And that’s why we’re here today, saving animals. I see it as something amazing. What he did in the past, if someone came and tried to do it today, they would fail, they wouldn’t succeed. All the processes, and the politics. Today I go nuts trying to do any little thing.”

Today, the descendants of those original donkeys, now third-generation Israelis, trot across the dusty plains and mingle with the oryxes and other exotic endangered animals that live at the Hai Bar. They have no idea of the political role that their grandparents played in the surrounding country where the struggle about who belongs rages on.